Why all the swallowtail butterflies?

You may have noticed that there have been a few different expeditions in the past few months focused on swallowtail butterflies. These specimens will be used for a larger project where we are planning to quantitatively look at the variation in wing morphology across and within swallowtail butterfly species. We have amassed approximately 1300 photos of swallowtail specimens from various museum and personal collections with the intention of having at least 10 males and 10 females from every Papilio species. Using morphometric analyses of landmarks on the dorsal and ventral wings, we will test the wing shape variation across species to see if there are correlations with sex, tropicality, geographic range size, and the number of congeners in the species’ range.

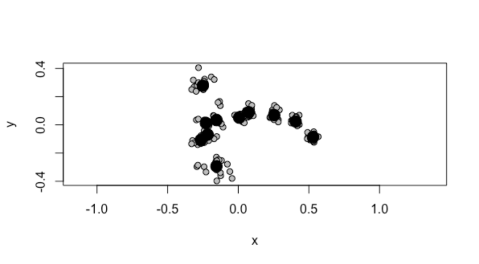

What do we mean by “landmarking”? This is an approach called “geometric morphometrics” where we select the same locations on a butterfly image in each image, and then we use some really neat tools that can find the best “fit” to a common “consensus”. For this project, we are using where veins in the butterfly wings meet the edge as our landmarks. Figure 1 shows an example of the ventral wing landmarks using this fitting method. The big black dots are the “consensus” landmarks and the variation around them in shown in the smaller grey ones. You can clearly see that some parts of the wing are much more variable than others. We know the orientation of the image below is a bit odd, but the variable landmark that is at the low point on the y-axis is near where the wing attaches to the body.

Now that all of the Notes from Nature swallowtail expeditions are complete, we will be working all summer to landmark these specimens and add more to our sample size for future analyses. If you are interested in the further ways we analyze morphological variation, give a holler and we can go into further detail. We will send along another update on this work later in summer, and thank you for helping us move forward with this research!

Figure 1. Plot for the x/y coordinates of the ventral wing landmarks for 27 Papilio specimens so far.

blog post by Laura Brenskelle

WeDigFLPlants Focuses on Spring in Florida’s Forests

Austin Mast, Florida State University

Miniature Fossils Magnified

Help scientists learn secrets of ancient seas

Today we drove down from the Natural History Museum in London to the jurassic coast of Dorset for the Lyme Regis Fossil Festival – where we are launching our latest crowdsourcing project – Miniature Fossils Magnified – just in time for #FossilFriday!!

The slides feature fossils of single-celled organisms called foraminifera, or forams for short, embedded in slices of rock.

Foraminifera are found in both modern and ancient marine environments and preserve well thanks to shells called tests.

The foraminifera specimens in the Miniature Fossils Magnified project lived in shallow tropical seas from 500 million years ago to the present day.

More than 2,000 microscope slides have been digitally imaged so far. Now the Museum needs as many people as possible to help transcribe the information on the specimen labels – such as the species name, location of where the sample material came from and its geological age – so that the data can be used for scientific research.

The project was set up by Dr Stephen Stukins and Dr Giles Miller, senior curators of micropalaeontology, and Science Community Coordinator Margaret Gold.

Dr Stukins says,

‘These fossilised organisms were very sensitive to their environment, so with this data we can better understand past conditions in the oceans and climate change through time.

‘All of this knowledge can be applied to what is happening now and in the future, giving us a better understanding of how our climate and oceans are changing.‘

Ocean organisms with a tale to tell

Foraminifera are among the most abundant shelled organisms in our oceans. A cubic centimetre of sediment may hold hundreds of living individuals, and many more shells.

Some forams spend their lives floating in the ocean. When they die, they sink to the seafloor and gradually become buried in sediment. Others – benthic foraminifera – live on or near the seafloor. The Miniature Fossils Magnified project features a collection of large benthic foraminifera.

Their sizes range from a few tens of microns in diameter – like a small grain of sand – to several centimetres across.

The material was collected during the mid-twentieth century as part of oil exploration in the Middle East. The scientists involved in dating rocks described many new foraminifera species and the slides were later given to the Museum due to their scientific value.

The data on the slide labels are invaluable. Analysing them can help us to understand how our climate and sea levels have changed, and also tell us the geological history of the area in which they were found.

A record of ancient environments

Foraminifera shells are often divided into chambers and can be quite elaborate, although simple open tube or hollow sphere forms exist.

Because of the abundance and variety of foraminifera, their fossils are extremely important for dating rocks.

They also provide a record of the environment where they’re found. Sea level and temperature changes affect the diversity and population sizes of foraminifera species, as well as the growth of individuals, impacting their size. Studying fossil foraminifera can therefore help scientists to understand past conditions.

Scientists can also study fossils from known periods of change to observe how foraminifera responded to particular climate and ocean conditions. If we then see similar changes to foraminfera living on tropical reefs in the future, this can help scientists to deduce how quickly the changes are happening and predict what may happen.

People-powered science

Dr Miller says,

‘The Museum collection of larger benthic foraminifera is one of the most significant in the world but is little used because much of it remains undigitised.

‘By helping to digitise this collection, you will keep it relevant for scientific studies long into the future.’

Unlocking Northeastern Forests: Complete!

Rhododendron arborescens (Pursh) Torr. / “sweet azalea”

Congratulations NfN volunteers for completing the New York Botanical Garden’s first expedition targeting vascular plants of New England!! Through your heroic efforts to catalogue over 2,300 specimens, scientists everywhere will soon have access to our complete historic collection of 300 different species of Oaks (Fagaceae), Blueberries & Rhododendrons (Ericaceae) found throughout the Northeastern US. That is no small feat, and you all deserve a tremendous round of applause!!

Or, more appropriately … *VIGOROUS RUSTLING OF LEAVES*

Fortunately, this fantastic success is only the beginning. NYBG staff and volunteers have prepared and photographed many more preserved specimens of other New England plants, which are now in need of examination by citizen scientists! Look out for the next phase of our project, Unlocking Northeastern Forests: Nature’s Laboratories of Global Change (Part II), and share in helping to advance our collective understanding of local, natural ecosystems–their historic baselines, and progressive shifts over time.

— Charles Zimmerman, New York Botanical Garden

Visionary Violets

Spring ephemerals are nature’s reward for surviving winter. These springtime sweeties emerge during the transition from winter to spring. They are an indicator that spring is (finally) on its way. Spring ephemeral plants thrive under unusual conditions. They only have access to sunlight for a brief period of time – they get shaded out by tree leaves once spring is in full swing. The Southeastern United States is home to several species of spring ephemerals. Help us show appreciation for these phenomenal plants while supplementing our database of herbarium specimens.

In an effort to transcribe our spring ephemerals, we wanted to start with a beloved spring star. Violets are a staple spring ephemeral plant. Violets are edible, medicinal, and beautiful – what’s not to love? Their emerald green leaves bring color back to the landscape. Violet flowers – although commonly purple – can be other colors as well! Despite the fickle spring transition we’re having in the Southeast, we’re trying to stay inspired and excited for warmer weather! Remind yourself the winter will eventually end by helping us transcribe these valiant violets!

— Alexandra Touloupas, North Carolina State University

Almost there… a finishing challenge

We are running a new expedition finishing challenge, for those with completion anxiety (like we do). Here are the expeditions closest to finished, in near order of effort needed:

1. Butterfly_New World Swallowtail Butterflies II

Classifications: 433 / 609, 71% complete but only 175 or so transcriptions left.

2. Herbarium_Unlocking Northeastern Forests: Nature’s Laboratories for Global Chang

Classifications: 6,886 / 7,089, 97% complete (200+ left)

3. Herbarium_Amaranthaceae: Cosmopolitan Allrounder

Classifications: 981 / 1,332, 74% complete (~350 transcriptions left)

3. Herbarium_Natural North Carolina’s – Adoxaceae – Elderberry and Viburnum!

Classifications: 8,480 / 9,288, 91% complete (still 700 left)

We really appreciate the help, and we’ll report when these get finished, so you can see who wins the challenge!

New 5000 badge!

We have recently added a new herbarium badge. This brings our count of herbarium badges to 7. The new “mature grove” badge is earned after completing 5,000 transcriptions on herbarium expeditions. There is something special about this particular badge. It was created by our own longtime Notes from Nature volunteer Mr. Kevvy!

Thanks to Mr. Kevvy for the contribution and congratulations for reaching this milestone!

Another Swallowtail Butterfly Expedition!

It’s about time—the New World Swallowtail Butterfly project has another expedition up. This is the last batch of McGuire Center specimen images I am collecting for a study on the relationships between morphological variation and geography. This collection provides an excellent record of morphological variation across the distributions of these species.

You may also come across some specimens that look different from the other McGuire Center specimens—their backgrounds are white foam with a white ruler for scale. These images were generously provided from the private collections of dedicated amateur lepidopterists. The specimens come from a hybrid zone between two species—Papilio canadensis, Canadian tiger swallowtail, and Papilio glaucus, Eastern tiger swallowtail. We are interested in understanding whether the hybrid species looks more or less like one of its parent species, an amalgamation of the two, or if it has begun to display morphological characteristics that are completely unique.

As with the previous Swallowtail expedition, remember that there are two images for each specimen—a front and a back. This is important, because in some cases, the labels in the image have different data written on each side. Thanks for your help, and look closely—some of these specimens provide a unique historical record of biodiversity that has since been lost!

Photo: Hannah Owens

Check back when the expedition is complete—we’ll have some exciting preliminary data for you!

Hannah Owens, Post-doctoral Fellow, University of Florida

3rd expedition of the NHM Chalcids launched in ‘Magnified’

Well, that came quick! We’re thrilled to now be launching our third and final batch of Chalcid slides on Notes from Nature!

Before you dive in, we thought you might like to find out more about these astonishing creatures in this article about the third-smallest winged insect ever known, which was discovered by our now-retired NHM colleague John Noyes and fellow researcher John Huber while on a research trip in Costa Rica:

The mysteries of the tinker bell wasp, one of smallest bugs ever discovered

Shots of a tinkerbella nana female taken under a microscope. From the top of its head to the bottom of its abdomen, the tinker bell wasp is 0.25 mm in length, about three times the width of the average human hair. (From the Journal of Hymenoptera Research)

Thank-you to everyone who gave us feedback about how we might make this last set easier to transcribe, with some additional information about where to find the required data on the labels.

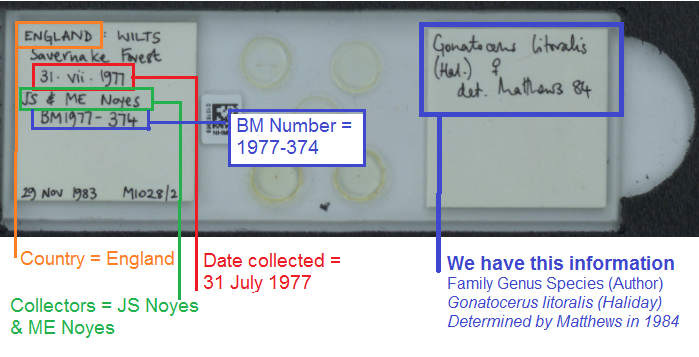

There are three collectors in particular who have made a very large contribution to this collection, so we thought it might be useful to highlight their slide labels and point out some information that might have been hard to interpret.

JS Noyes

John Noyes is a recently-retired colleague at the Natural History Museum who we still regularly see in our collection room pursuing his love of studying the Chalcidoidae – in fact he created a database that you may find to be a valuable resource when puzzling out scientific names: http://www.nhm.ac.uk/our-science/data/chalcidoids/. We like how neat and tidy his slides always are!

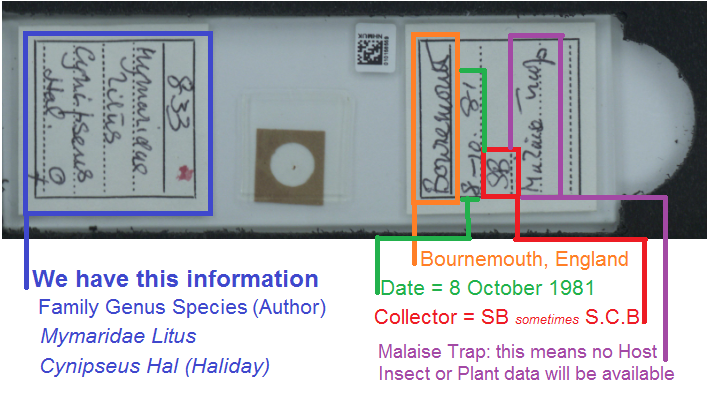

SB / S.C.B.

Sydney Charles Scarsdale Brown lived in Bournemouth, and seems to have gone on lots of local jaunts to collect the Mymaridae, using Malaise Traps. You can learn more about him in our post The Dentist who collected Fairyflies . His slides are some of the most frustrating in the collection because they’ll get your head flipping from one side to the other, but once you know that there are typically only a few pieces of data we need here, they are much easier to process.

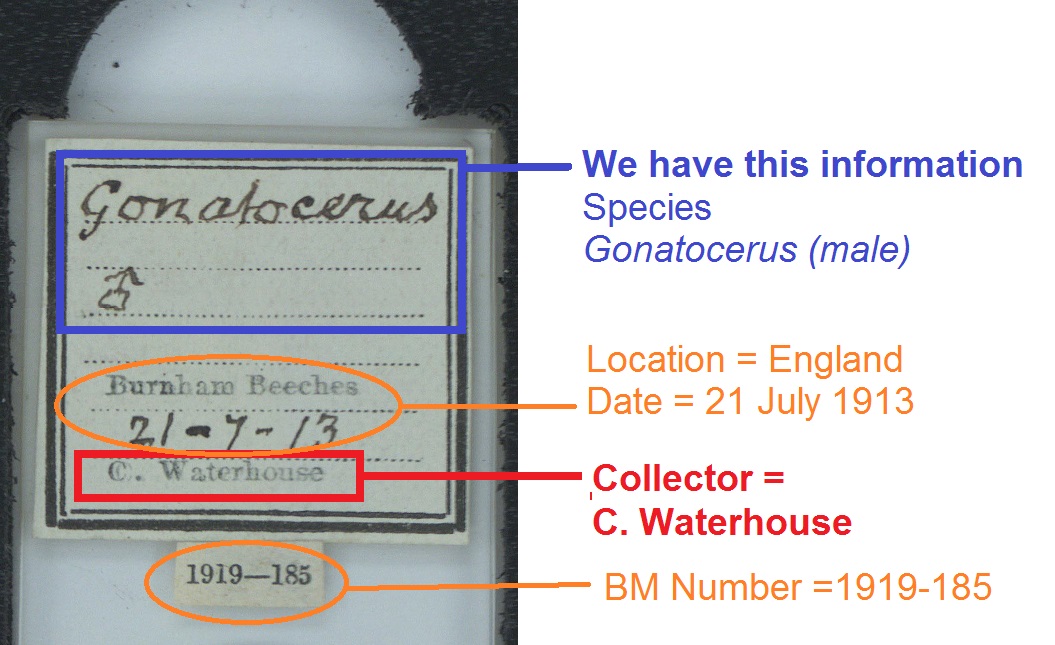

C. Waterhouse

Charles Waterhouse was an Assistant Keeper at the Natural History Museum, and seems to have preferred Richmond and Burnham Beeches to go on his collection trips for the Chalcidoideae. His slides will often have nicely printed labels with old fashioned hand-writing and a neatly typed British Museum registration number.

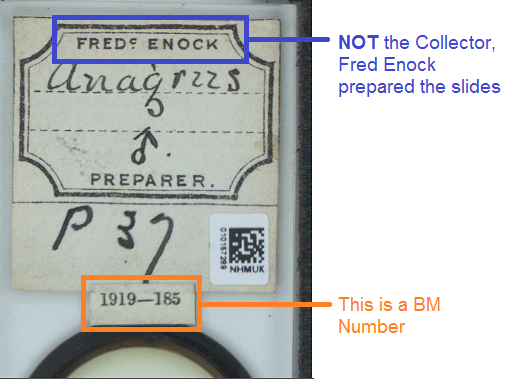

Fred Enock

You will also see many slides that have been prepared by Fred Enock, who worked at the Museum at the same time as C. Waterhouse, and was an Entomologist in his own right – naming many species (see if you can spot ‘enock’ written after any of the scientific species name on some of these labels). But more commonly found in our collection will be his preparation labels, where he is NOT the Collector. He’s quite an interesting person who we know a fair bit about – so keep your eyes peeled for a future blog post!

Fungus Among Us

Fungus Among Us considers the 19th-Century fungi collected in South Carolina by Henry William Ravenel

It’s not ‘your-celia’, it’s mycelia. Fungus Among Us asks volunteers to consider the myriad of mycelia that invade the earth, leaves, tree-bark and other substrates in their backyards. That’s exactly what Henry William Ravenel did back in the late 1840’s – except his backyard was either the malarial swamps of the lower Santee River or the diverse set of habitats found in and around Aiken, South Carolina. His exhaustive work culminated in the publication of the Fungi Caroliniani Exsiccati published between 1852-1856. The work consisted of five bound volumes called ‘Centuries’. Each Century contains 100 specimens of dried fungi that were painstakingly glued to the pages along with a descriptive label. In all, 30 copies of the five Centuries were produced for a grand total of 15,000 individual specimens that were carefully selected by Ravenel. Recognizing that his work was the first major effort to document the Fungi of North America since Lewis David von Schweinitz (1780-1834), Ravenel sent a copy to the Smithsonian Institution. Later that copy formed the nucleus of what is now the National Fungus Collection. The specimens presented here are from a copy that Ravenel presented to his Alma Mater – South Carolina College (now the University of South Carolina).

We encourage professionals, students, and citizen scientists from a variety of backgrounds (history, botany, mycology, etc.) to explore the world of 19th-Century Mycology and to help us by entering the label data visible on the image for each specimen. There is an interesting twist to this new expedition. Ravenel write his habitat information in latin. We don’t expect you to translate this text into to english, but some might find it interesting to research the meanings. Have FUN transcribing for . Among Us! Your hard work will eventually be displayed on the Mycology Collections data Portal, and will help update the entry for the Fungi Caroliniani Exsiccati.

To learn more about Henry William Ravenel and his contributions to science during the 19th Century please visit Plants & Planter.