The Digital Collections Programme has run two crowdsourcing projects on Notes from Nature in 2017. We wanted to say a massive thank-you to the 2,000+ volunteers who together have helped us to capture data from over 15,000 specimens this year. You have made a significant contribution to Science.

Crowdsourcing our data in 2017

We can digitally image individual microscope slides at a rate of up to 1000 slides per day, but we still need help with capturing the label information on each slide. Transcription is an essential part of our digitisation process.

By reading the labels and typing information such as the collection date and location into the relevant data fields, our digital volunteers make it possible for us to release this data freely and openly on the Museum’s Data Portal. This data is available worldwide for researchers to study and explore.

Over the past year we showcased our crowdsourcing projects at the Lyme Regis Fossil Festival, Science Uncovered 2017 and the global WeDigBio transcription event. We have also hosted 14 Visiteering Days, in which over 120 people took part. Anyone interested in taking part in our one-day Visiteering programme to support the Museum’s work can register online here.

The Killer Within: Wasps, but not as you know them

Fairyflies average at only 0.5 to 1.0 mm long

Our first crowdsourcing project within the Digital Collections Programme consisted of 6,285 microscope slides containing tiny parasitoid wasps called chalcids (pronounced ‘kal-sids’), which lay their eggs inside other insects. Chalcids are the natural enemies of many insect pest species that damage our food crops, and are therefore used commercially as biological control agents.

Thanks to the help of over 1,300 digital volunteers for the Museum, the scientific information contained on these microscope slide labels have now been fully transcribed and are currently being processed for publication on the Data Portal.

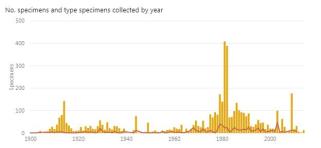

From this data we learned that John S. Noyes, formerly of the Natural History Museum and developer of the Universal Chalcidoidea Database, was our most active collector, that the majority of the specimens were collected in the 1980s and that the UK is the most prominently represented country in this collection.

Recently, we have been digitising the Museum’s parasitic louse slide collection – consisting of 70,667 slides at present. For each specimen, the whole slide has been imaged in to capture both the specimen and the labels.

From this collection we have isolated two subsets of louse specimens for two different crowdsourcing projects, each of which trialled a new platform for the transcription effort: lice from marsupial mammals – ‘Boopidae of Australasia’, hosted on DigiVol, and Lice of the Open Oceans, hosted on the Zooniverse.

Miniature Fossils Magnified: The smallest shells in the ocean

Foraminifera can help us learn how our ocean has changed over 500 million years

Our Miniature Fossils Magnified project features a collection of ~ 3,000 microscopic fossils, called foraminifera (or forams for short), embedded in slices of rock. The Museum has a strong tradition of foraminifera research dating back to the late 1800s, and the foraminifera collection – with approximately 250,000 slides – is one of the the most extensive in the world.

Foraminifera are microscopic single-celled organisms with shells (called tests), found in both modern and ancient marine environments. They either live on the sea bottom (benthic) or float in the upper water column (planktonic).

The 600+ digital volunteers have been helping to transcribe this label data so far and enabling research that can help us learn how our environment, climate and ocean have changed over 500 million years.

This project is almost complete, and with your help, we can start processing all of this data in the new year. As we process this data we look forward to sharing this data with you, and telling you of the scientific research that has thus been made possible.

If you have a few minutes to donate over the coming days, do join us on Notes from Nature to help finish off the Miniature Fossils Magnified Project. In the new year there will be new projects to join, and more outcomes to report.

There has been a flurry of activity at Notes from Nature these past few days, as a number of new Expeditions join us in the Plants section, and new sections for Aquatics and Fossils are launched, all in time for the 3-day

There has been a flurry of activity at Notes from Nature these past few days, as a number of new Expeditions join us in the Plants section, and new sections for Aquatics and Fossils are launched, all in time for the 3-day  It all kicked off at the Australian Museum, where the

It all kicked off at the Australian Museum, where the  As the planet turned, we were handed the baton here in London at the Natural History Museum, where we have a

As the planet turned, we were handed the baton here in London at the Natural History Museum, where we have a  We’re joined by our London neighbour

We’re joined by our London neighbour  And just a short trip down to the European continent, we are joined by the

And just a short trip down to the European continent, we are joined by the