Earth Day – Our One Year Anniversary

A year ago to this day, on Earth Day 2013, we launched Notes from Nature. Our choice of launch date reflects our hope that Notes from Nature can be a part of the Earth Day mission of creating a sustainable, green future. Every transcription that has been done over the last year brings a new data point onto our map of biodiversity. Taken together, we can finally assemble richer and deeper understanding of this amazing world all of us inhabit. With that knowledge, we can be better able to make wise choices about our planet’s future. Whether bugs, mushrooms, plants, birds or the myriad millions of species described or undescribed, our world is brimming with life, and our understanding deepened and stregthened with the meticulous efforts to collect and catalog that diversity.

So we are having a birthday party, in case you couldn’t guess from our front page, and we want you to join us! Come celebrate Earth Day and Notes from Nature both. Help us do something we never even thought possible — help us get our 500,000th transcription. We are that close, and we think it might be possible to get over the hump on our birthday. How cool would that be?

We mostly wanted to take the opportunity today to again thank every single transcriber out there for even tackling one record on Notes from Nature. We continue to be awed and amazed and appreciative of the effort you put in. We are pleased to have some new and exciting features coming your way at Notes from Nature in the next days and weeks and we hope we can keep this engaging and fun and productive in the long term for everyone. We also hope that the cool specimens and organisms you see on Notes from Nature speak for themselves. We think they tell the story of this green planet, on Earth Day no less, better than anything else.

Thanks again and take a second to wish us a happy one year anniversary!

FAQs and Useful Tools

We have put together a list of frequently asked questions and useful tools related to transcribing records. These are based on discussion threads in the NfN discussion forums (linked at the bottom). Please take a look, and let us know if there are any questions we missed or useful tools that you can suggest. These will eventually go on a page of the Notes from Nature website.

NOTE: The herbarium interface (SERNEC), now has it’s own FAQ. It can be found here: https://blog.notesfromnature.org/2015/04/14/updated-faq-and-useful-tools-herbarium-interface/

We really appreciate your input and all that you do for Notes from Nature. Thank You!

Common issues or questions that you may encounter while transcribing Notes from Nature records:

1.) Interpretation: In general, you should minimize interpretation of open-ended fields and enter information verbatim. This way, we can better achieve consensus when checking multiple records against one another (see below, on that process). However, some discretion would be nice. Here are examples:

Interpretation that you should make: Simple spacing errors (e.g. “3miN. of Oakland” should be “3 mi N. of Oakland”)

Interpretation you should leave to us: Don’t interpret abbreviations, we’ll sort that out. (e.g. “Convict Lk.” )

2.) Not in English: Transcribe exactly as written. Match label content to transcription fields as best as you can.

3.) Abbreviations: Transcribe exactly as written.

4.) Spelling mistakes: Transcribe exactly as written, unless you have looked it up and are absolutely certain of a simple spelling mistake. In this case, you can enter the correct spelling.

5.) Problem records: If you come across a problem record that may need to be addressed by a scientist, like a faulty image or a record with illegible handwriting, you can flag the record by commenting on it (e.g. with the hashtag #error) and indicate what is in error.

6.) Provinces: Provinces go in the Location field (e.g. Coastal Plain Province, Piedmont Province).

7.) Capitalization: Sometimes information may be in all capital letters on the labels. Unless this is an abbreviation, you should capitalize only the first letter of every word in your transcription (e.g. “COASTAL PLAIN PROVINCE” should be “Coastal Plain Province”).

8.) Many collectors: In many cases, collectors may be listed on different lines of the label with no punctuation separating them. In your transcription, please separate the collectors with commas.

9.) Missing information: What should you do when there is no information available for a field? When information is not given on the label, you should leave the field blank (in the case of open-ended fields) or select “Unknown” or “Not Shown” in the drop-down lists.

10.) Inconsistent collector names: You will often find several variations of the same collector name (e.g. “R. Kral” or “R.Kral”, “RWG” or “R.W.Garrison”). Use similar discretion when transcribing these variations as in the localities.

Interpretation that you should make: Simple spacing errors (e.g. “R.Kral” should be “R. Kral”)

Interpretation you should leave to us: Don’t interpret abbreviations, we’ll sort that out. (e.g. “RWG” should remain “RWG”)

11.) Many scientific names: For Calbug, you do not need to enter the species name (we have this info already), but if there is a scientific name that is different from what is listed in the record, put it into the “Other Notes” field. These could be old names, or plant host names.

For SERNEC Herbarium specimens, copy only the most recent name. This can be determined based on the date that appears on the ‘annotation label.’ If you do not see a date then enter the name that appears on the primary label.

12.) Variations and subspecies (SERNEC): Record the subspecies, but omit the scientific author’s name. So “Cyperus odoratus var. squarrosus (Britton) Jones, Wipff & Carter” becomes “Cyperus odoratus var. squarrosus”. “Echinodorus cordifolius (Linnaeus) Grisebach ssp. cordifolius” becomes “Echinodorus cordifolius ssp. cordifolius”.

13.) Scientific name (SERNEC): Provide the most recent name, whether it is a species name (a two-word combination of the genus and what is called the “specific epithet” in botanical nomenclature) or a one-word name that is at a higher taxonomic rank (e.g., just the genus or family name). Names at higher taxonomic ranks than species are used when a more precise identification has not been made. The species name should typically take the form of a genus name that begins with a capital letter and a specific epithet that begins with a lowercase letter. If any of the names are given in all capitals, such as “CYPERUS ODORATUS”, the name should be entered using the typical convention, “Cyperus odoratus” in this case.

14.) Latitude and Longitude: How do you enter latitude and longitude values, and where do these values go? Enter exactly as written, you can find symbols in Word or by searching online (e.g. 33° 62’ 22” N 116° 41’ 42” W). You can also produce the degree symbol ° using key combinations (alt + 0 on a mac; alt + 0176 on a PC, with the key pad on the right side of your keyboard). This information should go into the “Location” or “Locality” field, depending on the project you are working on.

15.) Special Characters: What should you type when there is a special character in a text string, such as a degree symbol or language-specific characters? You can do a google search for the symbol or copy and paste it from Microsoft Word symbols. There are also key combinations for common symbols. As mentioned above, you can produce the degree symbol ° using key combinations (alt + 0 on a mac; alt + 0176 on a PC, with the key pad on the right side of your keyboard).

16.) Elevation: Enter elevation verbatim into the “Other Notes” field for Calbug and the “Habitat and Description” field for SERNEC Herbarium records.

17.) County: If the county is not given on the label, please find the appropriate county using google search. However, if there are multiple potential counties for a locality, please leave the county field blank.

18.) Checking your transcription: You can use the link to the left of the “Finish Record” button (e.g. “1/9” or “9/9”) to check the information that you entered. Just click on any of the fields to make any necessary edits to your transcription.

19.) When is a record finished?: These blog posts describe the data checking process that uses 4 transcriptions of the same record to derive a consensus.

https://blog.notesfromnature.org/2014/01/14/checking-notes-from-nature-data/

http://soyouthinkyoucandigitize.wordpress.com/2014/01/14/412/

Some Useful Tools (discovered by NfN users)

Counties and Cities: Good tools for finding counties etc. are lists on wikipedia, there are lists of municipalities in each state of the USA (there are also similar lists for others). For example, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_municipalities_in_Florida (via the linkbox you can also change the state).

Mountains: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Lists_of_mountains_of_the_United_States

Uncertain Localities: Geographic Names Information System, U.S. Geological Survey.

https://geonames.usgs.gov/pls/gnispublic

Mapping tool with topo quads: To find uncertain counties or localitieshttp://mapper.acme.com

Collector Names: The Essig Museum of Entomology database has lists of collector names and periods of activity for many collectors you will find in Calbug records. http://essigdb.berkeley.edu/query_people.html

Hard-to-read text: Use “Sheen”, the visual webpage filter, for some hard-to-read handwriting written in pencil. (Tip was from the War Diary Zooniverse project) https://chrome.google.com/webstore/detail/sheen/mopkplcglehjfbedbngcglkmajhflnjk?hl=en-GB

Special symbols: You should be able to find symbols in word or by doing a google search and copy and paste. Here are a few:

– degree symbol for coordinates: °

– plus minus: ±

– fractions: ⅛ ¼ ⅓ ⅜ ½ ⅝ ⅔ ¾ ⅞

– non-English symbols: Ä ä å Å ð ë ğ Ñ ñ õ Ö ö Ü ü Ž ž

The Plant List: Search for scientific names of plants –http://www.theplantlist.org/

List of Trees: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Category:Trees_of_the_United_States

Integrated Taxonomic Information System (ITIS): http://www.itis.gov/

Essig database (for Calbug): Unsure if you spelled a collector name or species name right? It might also be worth checking similar entries already in the database, http://essigdb.berkeley.edu/.

NfN Discussion threads that this is based on:

FAQs

http://talk.notesfromnature.org/#/boards/BNN0000001/discussions/DNN000024q

Useful Tools

http://talk.notesfromnature.org/#/boards/BNN0000001/discussions/DNN00001vl

A Big Thank You to Ornithology Ledger Transcribers

Phase 1 of the Ornithological Collections transcription project has been successfully completed. Thank you to everyone who participated in the first stage of the project. Over a thousand users worked on the project producing nearly 100,000 transcriptions from 1037 register pages.

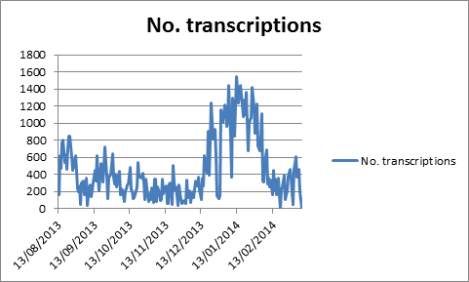

The resulting dataset is going to be tremendously valuable to Natural History Museum curators and researchers all over the world. We have included some pictures of museum specimens that now have useful electronic data thanks to your work as citizen scientists. Initial analysis suggests citizen scientists were especially busy over the mid-winter period.

Special mention must go to Snowysky, Estron21, OneUniverse, Dmbrgn, mbhook and AstroboyOW for their sterling work. We’d love to hear from you. But all contributions are valued and we’d love to hear from anyone who has participated in the first phase. Especially, as we enter an exciting second stage with six more registers that need transcribing. We hope you will all support us in this new phase ultimately aimed at getting all the Natural History Museum’s bird specimens on line.

With thanks and best wishes,

NHM Bird Group

Making Progress Clear on Notes from Nature

Notes from Nature is something of a departure for a Zooniverse project. Rather than a single organization asking for help with the exact same tasks, Notes from Nature is, like its subject matter, diverse. So we have labels of bugs, sheets of plants, fungal specimen labels, and ledgers of birds. And we have a lot – and I mean A LOT— of images that need transcription. Not only that, but each of those images are transcribed more than once—as mentioned in previous posts, right now each image gets 4 separate transcriptions.

All of this is preface to the main topic of this post – how do we measure “progress” with the tasks of transcribing all of this data. The science team on Notes from Nature has talked a lot about this, and a number of complexities related to making sure that the numbers are transparent to you, our volunteers. This post covers a fair amount about how to measure overall progress. We also know that there have been issues with transcription counts for individual volunteers. We believe that we have solved those issues, but we’ll cover those separately in another blog post.

So, here are two of the main issues we have been dealing with and some recent solutions that have been implemented across Notes from Nature:

Issue 1: Do we measure total number of transcriptions or total number of images that are “finished” (e.g. transcribed four times)?

Solution: We have decided to measure total transcriptions completed across all projects and within projects. This is a change from our previous strategy which had mixed and matched these different counts on different pages. We think the most obvious measure is overall effort put in, even if this means it is harder to know how many images have been done.

Issue 2: Should we even measure “completeness” within a project (e.g., Calbugs)? The reason this is an issue is that most projects on Notes From Nature have only posted a small subset of available images and there are many more “waiting in the wings”. We don’t want to say “hey, only a 1000 more images to transcribe” and then just a little later go “Oh! Just kidding, there are now 50000 more!” Our ultimate goal is to stage the many remaining images as smaller batches with compelling themes derived from their research or other societal values (e.g., all specimens from a particular national park or collected by an important historical figure). This will give us a chance to celebrate the success of completion more regularly. At the moment, we are seeking funding to do this.

Solution: We do want to show that progress is being made on the current batch of images on Notes from Nature, but we want to avoid any confusion if more images are made available once the current sets are close to be done. So we are showing a percentage that represents total number of transcriptions completed over the total number needed for a batch, but we link to this very blog post to explain why those may change. We are also providing some information on progress with the images themselves, and here we provide counts of “total images”, “active images”, “complete images”. Below is a definition of each of those terms:

active images – The number of images that are either in progress with being transcribed or waiting for transcription.

complete images – The number of images that have been independently transcribed four times

The University of Michigan Herbarium — Mecca for Macrofungi

This article was written by Matthew Foltz, who is the manager of the Macrofungi digitization project at the University of Michigan. We commissioned this article because most of the labels that are currently available for transcription in Macrofungi are from this institution. The University of Michigan Herbarium has an unparalleled history of contributions to the scientific study of fungi, and also for contributions to bringing an understanding of fungi to a general audience.

The University of Michigan Herbarium is internationally recognized as one of the leading repositories for natural history collections including Vascular Plants, Bryophytes (that is, mosses and related plants), Algae, Lichens, and Fungi. It has a rich history dating back to the late 1830s when state geologist Douglass Houghton conducted a geological survey of Michigan and deposited about 800 collections at the University of Michigan. The herbarium is now home to over 1.7 million specimens of plants and fungi collected from around the world, including about 280,000 collections of fungi.

Figure 1. The University of Michigan Herbarium houses over 1.7 million collections in 1,200 cabinets in a 16,000 square-foot climate-controlled range. Photo by M. Foltz.llections of fungi.

The University of Michigan Herbarium has strong roots in mycology. In 1921 the herbarium became its own department under the directorship of mycologist Calvin H. Kauffman. Directorship of the herbarium went on to several other mycologists in the 1900s including Edwin B. Mains, Alexander H. Smith, and Robert L. Shaffer. Calvin Kauffman was a mycological and scientific pioneer. His publication on the Agaricaceae of Michigan (as well as the series of fungal monographs that preceded it) was not only the most comprehensive for the state, but at the time it was also one of the best fungal surveys for North America. The family Agaricaceae contains the common grocery store mushroom.

To truly appreciate the impact that Kauffman and his predecessors have had on mycology, one needs to look no further than the Kauffman Lineage which is a part of Meredith Blackwell and Robert Gilbertson’s Genealogy of North American Mycologists. This lineage of education includes many of the most significant mycologists of all time, including some of today’s most prominent scientists.

The fungal collection at the herbarium is strong in both Macrofungi (mushrooms and shelf fungi) and microfungi (molds and mildews, etc.). Kauffman’s work was strong in the agarics (mushrooms) of the Great Lakes region, but he also collected in many localities across North American and internationally. Alex Smith followed in his footsteps and went on to become a leading expert of the agarics as well as other groups such as the gasteroid fungi (puffballs, earthballs, stinkhorns, etc.) and the boletes. Like Kauffman, Smith contributed to both the Great Lakes region flora, and the North American flora. Smith was a prominent collector and deposited over 92,000 specimens at the herbarium during his lifetime.

The value and depth of the Michigan fungal collection is strengthened by Dow Baxter’s extensive collection of wood-decay fungi, along with collections of agarics from R.L. Shaffer and hypogeous (underground) fungi from R. Fogel. The Michigan herbarium also owns several classical exsiccati (historical sets of reference collections), as well as historically important personal collections from H.A. Kelly, H.C. Beardslee Jr., and many others. In addition to macrofungi, Michigan also has extensive collections of microfungi from prominent mycologists including Bessie B. Kanouse (discomycetes), E.B. Mains (Uredinales, Geoglossaceae, insecticolous fungi), L.E. Wehmeyer (pyrenomycetes), F.K. Sparrow (aquatic fungi), and others.

Michigan mycologists have a history of supporting citizen science and collaborating with amateur mycologists and the general public. Alex Smith was an advisor and supporter of the premier amateur mycology group the North American Mycological Association (NAMA) in its early days.

Smith was a close friend to many of the top “amateur” mycologists such as Ellen Trueblood, Virginia Wells, Phyllis Kempton, and others.

These mycologists kept detailed records and notes with their specimens, and these important collections and their ancillary materials are deposited at the Michigan herbarium. More recently, Robert Fogel, a past curator of fungi at Michigan, was one of the first mycologists to create a website for learning about fungi in the 1990s (Fun Facts About Fungi).

The tradition of outreach continues today through the efforts of mycologist Tim James, the assistant curator of fungi at the herbarium. Recently, James has held lectures and forays for several amateur groups including the Michigan Botanical Club and the Michigan Mushroom Hunters Club. He is also leading the efforts at Michigan as part of the Macrofungi Collection Consortium, a nationwide project to digitize the fungal collections and make them available online to researchers and the general public. The digital records produced by that project are the ones posted here on Notes from Nature.

Figure 5. James lab (Umich) on a John Cage inspired mushroom foray with the Michigan Mushroom Hunters Club. Photo courtesy of T. James.

On behalf of the University of Michigan Herbarium, we thank you for your participation in this effort to transcribe information from these historical records.

An Ode to Collecting: following the path of an early 20th century dragonfly collector

As you enter information from old labels, have you ever wondered about the collector’s experience—20, 60, or even 100 years ago? Have you thought about what the river, lake or meadow was like? Or how the place may have changed since the collector was there? I have, and so I spent a couple of years revisiting sites originally sampled by C.H. Kennedy for dragonflies in 1914-1915. Check out my recent blog post on this experience, entitled An ode to collecting: following the path of an early 20th century dragonfly collector.

Checking Notes from Nature Data

You may have wondered how we will use the data you are transcribing… Especially after you spend a few minutes trying to figure out the meaning of some unclear handwriting, and are uncertain whether the year on the label actually says “1976” or “1879,” or if the locality is “Vino” or “Vina” in California.

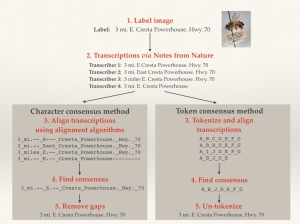

The first step in using Notes from Nature transcription data in research is checking data quality. Each specimen is transcribed independently by four different users, so mistakes in a single transcription do not impact the accuracy of our data very much. But how do we determine the right one out of the multiple transcriptions? For controlled fields such as country and state, this is simple: we perform a “vote-counting” procedure, where the value with the most “votes” is considered correct. However, this is much more difficult for open-ended fields such as locality or collector names.

One of the early approaches was to quantify differences between transcriptions. We did this by using the Levenshtein edit distance, named for the Russian information scientist, Vladimir Levenshtein, who developed a way to quantify the minimum number of single-character edits required to change one string of text to another. For example, “12 mi W Oakland” and “12 mi. W Oakland” would have a score of 1 because of the period after “mi”. We then looked for highly similar pairs of transcriptions for each specimen (pairs that were separated by the smallest edit distance), and then chose one of the pair. Our assumption was that if two separate transcriptions are almost identical to one another then either one must be very close to being correct. However, this assumption becomes violated if users are consistently wrong (either because the label is partially obscured, or the handwriting difficult to read, etc.). Furthermore, this was not a true consensus in the sense that our algorithm only decides which transcription out of the four is the best.

During the Hackathon last month (discussed in an earlier blog), it was quickly obvious that this approach was not ideal. In discussions with other researchers and experts, we developed an approach to combine the best elements of each individual transcription into a locality string that was greater than the sum of its parts. We did this using a concept from bioinformatics known as “sequence alignment.”

Genetics researchers and molecular ecologists use sequence alignment to match up multiple DNA or amino acid sequences in studies of evolutionary history or DNA mutation. To evaluate alignment, algorithms look for particular strings of amino acids or nucleotides within multiple sequences, and match similar or identical regions. Even closely related sequences, however, are often not identical and have small differences due to substitutions, deletions or insertions. So, alignment algorithms use complicated scoring mechanisms to generate alignments requiring as little “arrangement” as possible. The goal is to balance potential insertions, deletions and substitutions in characters from one sequence to the next.

In Notes from Nature data assessment, we use this method and assume that differences between transcriptions in a particular location may be due to substitutions. Or, we introduce gaps so that two separate chunks of sequence might be better aligned. This is especially useful if there are certain chunks of text within an individual transcription that are not consistently shared among all other transcriptions.

We implemented sequence alignment in two ways, using token and character alignment. For token alignment, we converted each chunk of text (usually individual words) and assigned each unique chunk a “token.” We then aligned the tokens. For character alignment, we compared each character in the text string directly. This proved to be the better method, as we inherently had a lot more information for the alignment software to work on.

An Illustration of Character and Token Alignment

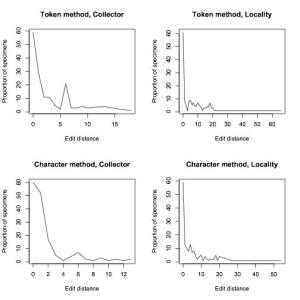

To compare how well our algorithm was doing, we manually transcribed around 200 of Calbug’s specimens, and ran our algorithm on user transcriptions. 70% of the consensus transcriptions were either EXACTLY identical or within 5 edits to our manual transcriptions. While this result is preliminary and we’re still working on improvements, it is worth mentioning that the testing data set included quite a lot of the very worst examples of handwriting on a teeny tiny label.

Proportion of records that were exactly identical or within 5 edits to manual transcriptions

| Method |

Field |

Proportion exact (n =158) |

Proportion < 5 edits |

| Token |

Collector |

37.3 |

74.1 |

| Token |

Locality |

38.6 |

58.8 |

| Character |

Collector |

38.0 |

88.0 |

| Character |

Locality |

37.3 |

69.6 |

Proportion of specimens that were a certain edit distance away from our manually-transcribed set of specimens

In closing, we’d like to emphasize the importance of typing exactly what you see in the open-ended fields for collector and locality. A certain degree of interpretation may be necessary. For example, if there are no apparent spaces between words (e.g. DeathCanyonValley) it would be useful to add them. But, it is often very difficult (probably impossible) to derive a consensus if the inconsistency of label data is compounded by inconsistencies in data entry. We have ways of dealing with the huge diversity of abbreviations, so it would be helpful if you enter them as they are when you see them with minimal interpretation. The overall lesson from our data quality comparisons is that so far we are doing great, thanks to your careful work!

Want to learn more? Check out a related blog post, here.

—

By Junying Lim

CITSCribe & Notes from Nature Hackathon

The CITSCribe Hackathon, co-organized by Zooniverse’s Notes from Nature Project (www.notesfromnature.org) and iDigBio (www.idigbio.org), brought together over 30 programmers and researchers from the areas of biodiversity research and digital humanities for a week to further enable public participation in the transcription of biodiversity specimen labels. There are approximately 1 billion biodiversity research specimens in US collections alone, but it is estimated that information from just 10% of them is currently digitized and online. Digitization of these specimens gives researchers access to vast quantities of information in their investigations of timely subjects such as climate change, invasive species, and the extinction crisis. The magnitude of the task of bringing those specimens into digital format far exceeds current capacity and requires new, Internet-scale approaches to engage the public to help with the task and learn more about biodiversity collections. Participants in the hackathon were energized by the opportunity to work on groundbreaking citizen-science projects with immediate and strong impacts in the areas of biodiversity and applied conservation.

The event opened on December 16, 2013, at iDigBio’s University of Florida (Gainesville, FL) center with the co-organizers Rob Guralnick (University of Colorado, Boulder) and Austin Mast (Florida State University) introducing the group to the process of digitization of biodiversity specimens, the heterogeneity of specimen labels, and the role that public participation tools and public participants play in the digitization workflow. This was followed by a brief introduction to the development tracks that sub-groups might like to tackle during the week: (1) interoperability between public participation tools and biodiversity data systems, (2) transcription quality assessment/quality control (QA/QC) and the reconciliation of replicate transcriptions, (3) integration of optical character recognition (OCR) into the transcription workflow, and (4) user engagement. The brief introductions and expressions of interest that followed made it clear that there would be a critical mass of complementary interests and competencies in each track for the week (Yay!).

After Cody Meche (an Agile Trainer and Coach at Davisbase Consulting) energized the group with a talk on agile development best practices (thanks for volunteering your time, Cody!), Alex Thompson (iDigBio) presented some of the digital resources that iDigBio had assembled prior to the hackathon (including a Vagrant script to build a virtual machine for the Notes From Nature web interface) and helped the programmers set up their development environments in a “Tech-up!” session. Yonggang Liu presented the new iDigBio Image Ingestion Appliance for the iDigBio Cloud—a storage resource for public participation tools. The hackathon participants then self-organized into development tracks to plan deliverables and the development roadmaps in the Team-up!, activities that culminated in presentations to the whole group in a Stand-up! session after lunch on Day 2.

Huge progress was made in a series of Code-sprints and Stand-up! sessions that composed much of the second-half of Day 2 and the full Days 3 and 4. These were punctuated by occasional Mix-up! sessions in which either pairs of development teams met together to discuss areas of overlap or the participants were completely randomized into new groups to discuss new directions not yet taken. A call-in from Laura Whyte, the Director of Citizen Science at Adler Planetarium, provided an exciting overview of the latest activities at Zooniverse, including GalaxyZoo Quench (a project that is engaging the public from the process of data collection to data analysis to manuscript writing) and ZooTeach (a site where teachers can find lesson plans that complement Zooniverse projects). And an excursion to the Florida Museum of Natural History (including its colorful Butterfly Rainforest) on Wednesday afternoon provided a bit of a breather from all of the coding.

On the final day, hackathon tracks presented their final Stand-up!—a parade of creative and useful solutions for public participation in transcriptions. The interoperability track (Alex T., Ted H., Matthew M, Ed G., Robert B., Greg R., Yonggang L.) introduced their code to produce a Darwin Core Archive that describes discrete projects (sometimes called “Expeditions” or “Missions”) for ingestion by public participation tools and export from those tools back to the data providers. This includes code to generate descriptions of the project (e.g., taxonomic and geographic scope) in Ecological Markup Language along with record-level description of images and digitization projects using Audobon Core and Darwin Core. Parts of this code were added to a beta version of the iDigBio image ingestion appliance and Symbiota, a biodiversity data management tool. Much of the further development in this area will involve creation of a public participation management tool to create and manage projects of this type and download and process publicly generated data.

The QA/QC track (Jun L., Tony K., Al M., Chuck M.) tackled a big challenge in citizen science transcription—how to take the outputs from the citizen science transcription products and assure the highest quality end result. Team QA/QC introduced an innovative pipeline for building consensus from multiple transcription replicates using characters or, alternatively, tokens using the MAFFT alignment tool—a tool typically used for DNA sequence alignment. They demonstrated ca. 35% agreement between the consensus that the two methods generate and gold standard data (transcribed by highly trained digitizers) for exact matches. They also generated script to normalize the name strings (e.g., from “A. R. and F. T. Smith” to “A. R. Smith, F. T. Smith”). Much of the further development in this area will involve optimizing the alignment algorithm for this task and making the consensus builder into a web service that can take input replicate transcriptions and output a consensus transcription.

The integration of OCR track (Go Team Ll Ll!; William U., Deb P., Andrea M., Sylvia O., Miao C., Jason B.) created word clouds (using n-gram scoring, faceting, and Solr for indexing + Carrot2 for visualization) and explored their use in two steps of the pipeline: a step in which the public participant selects a subset of specimens with a word of interest from the word cloud and a data cleaning step, where infrequent words are highlighted by the system. They also created an interface for exploring the words using histograms, rather than word clouds. Much of the further development in this area will involve integration of the word selection step into public participation tools and integration of the visualization for data cleaning into a processing tool, such as the public participation management system.

The user engagement track (Go Team Honey Badger!; Julie A., Matthew B., David B., Paul F., Lisa L., Paul K.) made progress on a diversity of useful fronts. Their completed “ditto” function code to autocomplete Notes from Nature fields using previous entries with key-binding is sure to make data entry in that system far more efficient. Other code created by that group created functionality in Notes from Nature to see all target fields at once in a single window for easy tabbing between them and to flag specimens with explanations for skipping them (e.g., specimen label obscured, specimen label illegible). The group brainstormed dashboard functionality for public participation tools, created a mock-up for a dashboard in Notes from Nature, and coded a dashboard (tentatively called My Dashboard) in Atlas of Living Australia’s Biodiversity Volunteer Portal. These dashboards provide such things as a map of specimens transcribed by the public user, the user’s badges, and completed missions in which the user participated. The group also produced white-papers on ideas to encourage user sign-in, gamification ideas for Notes from Nature and the Biodiversity Volunteer Portal, and classification of user experience. Much of the further progress in this area will involve testing and implementation of this new functionality in the production versions of Notes from Nature and Atlas of Living Australia’s Biodiversity Volunteer Portal.

Hackathon participants represented a broad range of career stages—undergraduate students, graduate students, postdoctoral scholars, computer programmers, and university faculty—and institutions, including the Adler Planetarium, University of California–Berkeley, Cornell University, Harvard University, King’s College London, Australian Museum, Smithsonian, New York Botanical Garden, Botanical Research Institute of Texas, Illinois Natural History Survey, Atlanta University Center, National Ecological Observation Network, and many others. Digital humanities projects represented at the hackathon included the University of Iowa Libraries’ DIYHistory Transcription Project, Indiana University’s Data to Insight Center, the Outreach Ethnomusicology project, and the FromThePage.com transcription project. Biodiversity projects represented included Notes from Nature, iDigBio, VertNet, Atlas of Living Australia, Symbiota, Filtered-push, Morphbank, Smithsonian Digital Volunteers, and the Biodiversity Heritage Library.

Documentation of the hackathon can be found at the CITSCribe wiki (https://www.idigbio.org/wiki/index.php?title=Transcription_Hackathon). This includes a complete participant list and many recorded presentations. Hackathon participants used the hashtag #CITSCribe, and a few additional photos are available at https://www.facebook.com/iDigBio/photos_stream.

Cookies From Nature

‘Tis the season to be thankful for friends, family, and citizen science. And you can combine all three by making Notes from Nature cookies to serve to those around you:

| Ingredients | Preparation |

|---|---|

| 2 3/4 cups all-purpose white flour 1 1/4 cups granulated sugar 1 teaspoon baking powder 1/4 teaspoon table salt 2 large egg yolks 3/8 cup sour cream 1 tablespoon vanilla 1 1/2 sticks (12 tablespoons/175 g) unsalted butter |

1. Melt the butter and set aside to cool slightly.

2. In a large bowl, combine dry ingredients and whisk together. 3. In a smaller bowl, whisk egg yolks, sour cream, and vanilla until combined. Slowly add melted butter, whisking constantly, until mixture is smooth and homogeneous. 4. Pour wet ingredient mixture into dry ingredients; mix until flour is completely incorporated and the dough roughly makes a ball. 5. Turn dough out onto sheet of parchment paper (lightly floured if necessary), and separate into two halves. Form each half into a book-shaped rectangle and wrap with cling film. |

Once this is done, put the dough in the fridge for an hour or so to chill it out somewhat. You want the butter in the dough cold enough to keep its shape and not stick to things, but warm enough that the dough doesn’t break when you roll it out. Once you’re there, knead the dough a bit to get rid of any cracks and form a ball shape, then roll it out on a piece of parchment paper. In my experience the dough doesn’t stick to the paper or the rolling pin, but you can use a bit of flour here if necessary to prevent sticking.

Just before you start rolling, preheat the oven to 325F (160C). Roll the dough out to about 1/8-inch (~3 mm) thickness. Then start cutting out shapes. If you have cookie cutters for leaves, butterflies, and other Notes from Nature objects, great! I didn’t, though, so I free-handed them instead, with the help of a friend.

This is a pretty standard recipe for butter cookies, and was adapted from Cook’s Country. The key point here is that you can knead it, roll it out, cut out shapes, collect scraps, knead them, roll them out, etc… for as long as you like, and the dough won’t get tough. So go ahead — get creative with the shapes!

If you’re doing this freehand, it might take a few tries to get a decent moth shape. Unless you’re my assistant/friend, who was awesome from the start.

Bake until the edges of the cookies are golden brown. The timing depends on the size of the cookies and whether or not you have a convection/fan oven. The original recipe was for a conventional oven and recommended 16 minutes per cookie, which will need to be shortened considerably if you have small cookies and a fan oven. Might be best to set a timer for 7 minutes and then rotate the cookie sheets and check for doneness.

Of course, when you bake cookies of wildly different sizes on the same sheet, it’s not easy to get them all to “golden brown” at once.

To decorate, you can make a simple icing with 1/2 cup of icing sugar and 1 tablespoon of milk (plain icing) or lemon juice (sweet-tart icing). You can also use food coloring or a drop or two of flavor extracts like almond or mint. The icing can be the decoration by itself, or it can be used as an underlaying glue for various sprinkles and edible beads, or it can be layered over melted (then chilled to set) chocolate. The sky is the limit for decorating, or you can just leave these plain, as the cookies are delicious on their own. But a little sparkle can be fun too:

I brought these into work the next day, where my Zooniverse colleagues were happy to help me taste test.

Which one is your favorite shape? What would you add? There’d be plenty of room for it: the above picture shows about one-quarter of the cookies this recipe made. You won’t be lacking for cookies. Enjoy!